How GPT-3 Works

Original Article, published in Nerd for Tech on Medium:

How GPT-3 Actually Works, From the Ground Up

When I first heard that OpenAI released a new and improved version of their language model last June, I was beyond elated. And seeing its full potential completely exceeded my expectations. With a sophisticated architecture and 175 billion parameters, GPT-3 is the most powerful language model ever built.

In case you missed the hype, here are a few incredible examples. Below is GPT-3’s response after being asked to imitate a specific psychologist:

And this is a demonstration simple application that generates code for a web layout: Original post

How does this work??? It’s literally a robot that can do virtually anything you ask it to. To understand where it all comes from, we’ll have to look at the field of NLP as a whole, expand on OpenAI’s specific GPT techniques, and finally, how they managed to train a model this staggeringly huge.

What is NLP?

Natural language processing (NLP) is the study of programming computers such that they can parse and generate text that is readable by humans. Right now, it’s a subtopic of machine learning, because ML is the most advanced method that enables computer programs to understand the complex nuances behind written language. To learn more about the relationship between the fields of NLP and machine learning, you can check out **this** article!

GPT-3 is fundamentally a language model, a specific type of machine learning model that analyzes written text. An example of a smaller-scale language model is the text prediction feature on your phone. Most mobile operating systems have a keyboard that suggests the next word as you’re typing, which is similar to the basic concept behind GPT-3. But how does this work?

Language models: The basics

At its most fundamental level, a language model is a device that assigns a probability to potential sequences of words (1). Trained on massive amounts of real, human-written data, it draws associations between words, and, when given an *n-*length sequence of random words, it can calculate the probability of that sequence existing in normal, human-written text based on the rules for context that it developed from its training data.

Language models can be useful for a variety of NLP applications, including speech recognition, translation, optical character recognition, and text parsing. This method is so important because it essentially verifies whether a series of words is legitimately “natural” — whether it can actually be processed by humans — enabling the algorithm to understand how to generate text patterns that look like they were created by humans.

To return to the mobile phone text prediction example: say you have a sequence of words. The algorithm needs to continuously predict the next word, until you have a complete paragraph. To understand which word should come next, the algorithm takes the last few words as input, and based on the probabilities it has assigned to sequences of words, it can return the word that is most “likely” to naturally come next.

The transformer language model

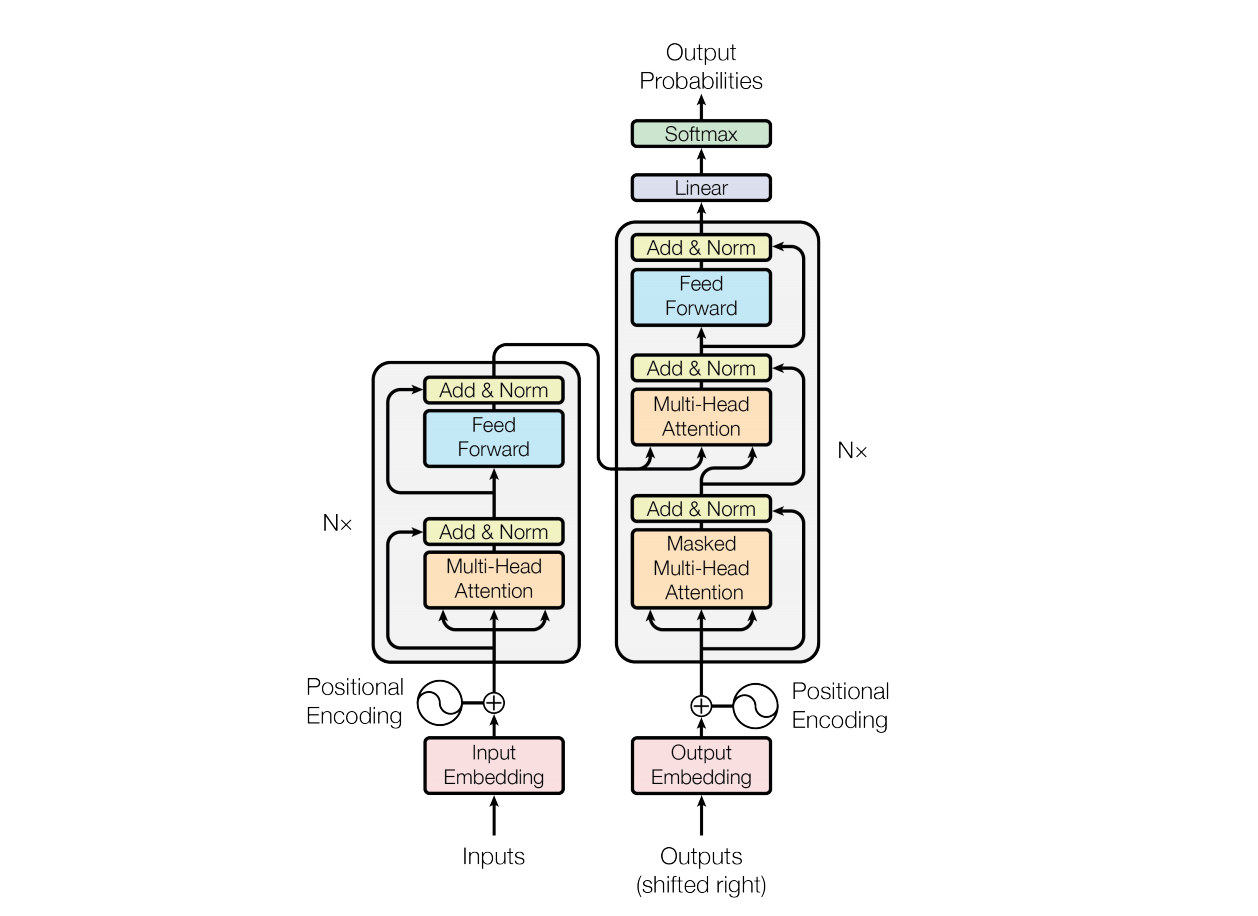

Transformer models are a type of neural network designed to process sequences — transforming an input sequence to an output sequence. In the case of a language model, these are sequences of words. In fact, the acronym GPT actually stands for “Generative Pre-trained Transformer.”

The key part of transformers is a process called attention, which enables the model to understand which words are most important to consider when evaluating which sequence to produce. In each iteration, numerical weights are assigned to each word, which are then analyzed by the decoder, thereby determining the key aspects of the input text upon which the output should be based.

Efficiency and comparison

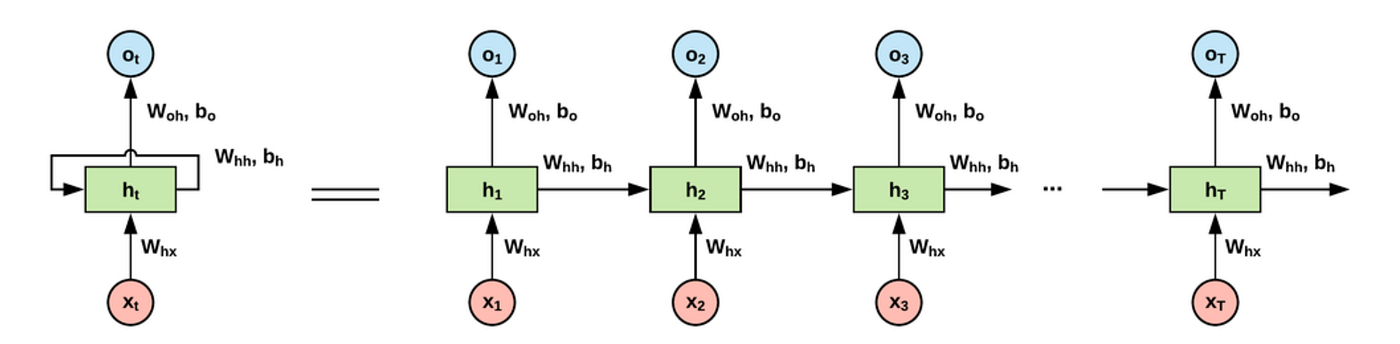

The nature of NLP techniques generally consists of human-readable input and output. If the task is predicting the next word in a sequence, some kind of algorithm will have to look at previous words as input and provide the next word as an output. Up until recently, the best way to do this was using a recurrent neural network (RNN), an architecture that grabs the previous sequence of words, adjusts a probability vector, and repeats this process for each new word.

An illustration of an “unfolded” recurrent neural network. Credit

Unfortunately, this process becomes extremely inefficient for large sequences of words. Since the vector has finite length, once it contains a certain amount of information, it must start replacing old probabilities to make room for new ones. Ultimately, the RNN simply “forgets” any relevant information that it saw before a certain point, which often leads it to follow a chain of reasoning that has nothing to do with the original topic.

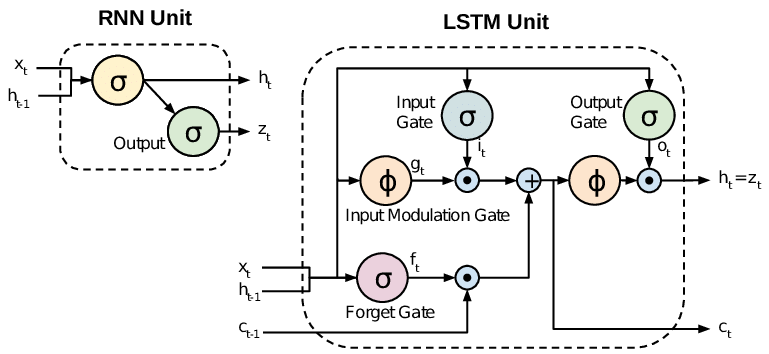

A more modern take on this task uses a type of recurrent neural network called “Long/Short-Term Memory” networks, or LSTMs for short. Instead of instantly forgetting every piece of information beyond a certain point, LSTMs are actually trained to learn what to forget, ensuring that the vector that is being recursed contains only the most relevant information. That is, what the LSTM thinks is the most relevant information.

The thing is, LSTMs only work up to a limit too: the language modeling vector still has finite length, so at some point, processing long and complex pieces of text again becomes computationally expensive. In addition, LSTMs have shown to experience trouble deciding what to forget in large contexts.

Conventional RNN unit compared to an LSTM unit. Credit

Interestingly, the issue shared by LSTMs and RNNs is sort of like waking up drowsily after a bad night’s sleep, and then barely being able to speak coherently since your working memory is reduced…

🫰🫰 Pay Attention!!

The best way to understand attention on a simple, conceptual level is that instead of deciding what to forget, attention decides what to remember before a probability is even computed. This enables the algorithm to prioritize which pieces of text to pay attention to. Below is a diagram of the architecture of a transformer, taken directly from the original 2017 paper introducing it:

Transformer architecture diagram. Source

Another advantage of transformers is that it can parse through multiple parts of a piece of text simultaneously. In other words, the entire algorithm doesn’t need to run every time you want to generate a new word in a sequence — it can input and output large paragraphs in one go, which, in addition to improving the algorithm’s “attention span,” makes computing significantly less time-consuming.

Training GPT-3

Training is one of the most critical components of developing a machine learning model. Before training, the algorithm is a machine with a bunch of networked boxes that have no relation to each other. Training is so important because it teaches the model how to process a given input; it’s how the machine “learns” which sequences of words are appropriate for a certain context.

GPT-3 was trained using “next-word prediction,” a kind of training in which — yep, you guessed it — it predicts the next word in a sentence. Here’s a diagram of how the training process works:

https://miro.medium.com/max/1400/0*7WXQvSZbGHQSQOV7

As you can see, the “parameters” are essentially the individual “boxes” of numbers used to analyze the relationships between words. Untrained GPT-3 has no idea how to do this; all of its number boxes have a random value — but a complex training process assigns appropriate values to each parameter, enabling the model to process information accurately. This is the basic premise of a neural network too!

When this model’s predecessor, GPT-2, was released in 2018, the world was blown away by its acuity. At 1.5 billion parameters, its size was considerable — but the craziest part was that GPT-2 was’t even fully trained. What would happen if a similar transformer was trained with even more data, creating a network orders of magnitude larger than the previous?

The primary distinction between GPT-3 and similar models is its sheer size. With 175 billion parameters, its magnitude easily surpasses that of its closest competitors (2). It was estimated that training GPT-3 would have cost at least $4.6 million. In addition to its staggering capabilities, that’s probably another reason why OpenAI is only releasing GPT-3 through an API to select individuals.

Looking forward

GPT-3 is one of the most sophisticated language models to date, but as time goes by, similar models are becoming more and more expansive. The difference between GPT-3 and GPT-2 highlights the incredible potential of a modern language model simply trained with a large set of data and many parameters.

Personally, I can think of dozens of awesome applications for this technology. The first that comes to my mind is adding NLP to the classroom — such models could be used to create quiz questions and possibly even provide feedback on written work. Many programmers are beginning to think that GPT-3 will soon even be used to complete basic elements of their jobs, demonstrated by its ability to generate code. GPT-3’s vast array of use cases demonstrate promise for a future in which humans can seamlessly interact with machines.

I hope you learned something new! Feel free to learn more about me on my personal site or connect on LinkedIn.

Footnotes

- It’s not completely true that language models only process sequences of words — in reality, they can process any unit of characters, including words, phrases, word segments, and individual characters themselves. GPT-3, however, parses and generates text one word at a time.

- In fact, GPT-3 is even further ahead of its competitors in its capabilities because it hardly requires any specific training to complete many sophisticated tasks. This concept is called “few-shot learning” and has begun to garner wide interest in the machine learning community. In this context, what I referred to in this article as “training” was actually “pre-training,” where the real training is the additional data that the user supplies, specific to the task at hand.